New Angled Crime trend on

Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh

Abstract: Mobile Financial Services significantly contributes in the development of a country – either developed or developing. From law enforcement point of view, the traceability of a mobile phone provides a strong investigative and evidentiary tool. The combination of security and portability inbuilt in the products increases, I should say, should increase the safety of users by decreasing their exposures to common crime. This in turn should lead to an actual fall in societal violent crime.

The role of our central Bank through developing a number of guidelines and regulations to administer the new developing sector is praiseworthy. But updating financial legislation alone is not sufficient until we focus on criminal justice statutes. Specifically, updating evidentiary and criminal procedure statutes with Mobile Financial Services is very important. The range of cooperating stakeholders needs to be expanded to include not only the entities tasked with regulation but also Government agencies tasked with investigations and prosecution, such as the police, prosecutorial service, judicial sector, anti-corruption authorities and FIUs; and agencies who receive P2G payments, including tax authorities, traffic police, and court authorities. In addition to development benefits, MFSs bring a host of security benefits to both citizens and governments. Nonetheless, MFSs also raises potential challenges for consumers, mobile finance products and governments. MFSs are being used for payments between criminals and within hierarchic criminal organisations. Fraud, extortion and corruption also seem to be assisted by the systems, including because of increased velocity of activity. Criminals also widely use MFS for intra- or inter- group payments locally and regionally. Such criminality can be reduced through well-implemented CDD, alongside dynamic training and education.

We also see lacking necessary education among the stakeholders. Hence, Mobile finance providers should engage in robust stakeholder education efforts, targeting consumers, agents, and government officials, with the aim of increasing knowledge of how mobile financial systems work, what their vulnerabilities are, how to mitigate them, and how they can be of net benefit to each type of stakeholder.

Regional information sharing efforts should also be strengthened, bringing together both government and private sector actors to identify trends in mobile finance-related crime and better develop mitigation efforts.

In the midst of crime targeting mobile finance users as a continuing challenge, we should find out a way how to further enable the opportunities and mitigate the vulnerabilities.]

Keywords: ACC, Agent, B2G, B2P, branchless banking, Bank-based model, Bank-led model, Customer due diligence or CDD, e-money, Financial Action Task Force (FATF), Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), G2P, Know Your Agent or Agent due diligence, Know Your Customer or KYC, Money laundering, Mobile banking, m-banking, Mobile financial services (MFS), Mobile network operator (MNO), P2B, P2G, P2P, Police.

Basic Terminology of Mobile Financial System

The Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) defines basic terminology related to Mobile Financial System. © 2012 (July), Alliance for Financial Inclusio.

1. Agent: Any third party acting on behalf of a bank or other financial services provider (including an e-money issuer or distributor) to deal directly with customers. The term ‘agent’ is commonly used even if a principal agent relationship does not exist under the law of the country in question. Using existing retail outlets as agents, particularly those near low-income populations, can help drive down the delivery costs of financial services for underserved populations. Agents may (if permitted under local law) engage sub-agents to carry out activities on behalf of the financial services provider. A mobile financial services provider may also engage an agent network manager to help select, train, manage, and oversee agents.

2. B2G: Business-to-government payment. B2G payments include taxes and fees.

3. B2P: Business-to-person payment. B2P payments include salary payments.

4. Balance and transaction limits: Limits placed on account transactions, such as maximum balance limits, maximum transaction amounts, and transaction frequency. Why are balance and transaction limits important? Limits on accounts may help to reduce the risk of money laundering and terrorist financing and allow KYC rules under a risk-based approach to be simplified.

5. Banking beyond branches / branchless banking: The delivery of financial services outside conventional bank branches. Banking beyond branches uses agents or other third party intermediaries as the primary point of contact with customers and relies on technologies such as card-reading point-of-sale (POS) terminals and mobile phones to transmit transaction details.

6. Bank-based model: A mobile financial services business model (bank-led or nonbank-led) in which (i) the customer has a contractual relationship with the bank and (ii) the bank is licensed or otherwise permitted by the regulator to provide the financial service(s). In bank-based models, the bank often outsources certain activities to one or more service providers (such as an MNO) for the transmission of transaction details and sometimes the maintenance of clients’ sub-accounts.

7. Bank-led model: A mobile financial services business model (bank-based or nonbank-based) in which the bank is the primary driver of the product or service, typically taking the lead in marketing, branding, and managing the customer relationship.

8. Cash-in: The exchange of cash for electronic value (e-money).

9. Cash-out: The exchange of electronic value (e-money) for cash.

10. Cash merchant: A type of agent that only conducts cash-in/cash-out services.

Cash merchants are often considered less risky (because of their limited functions) and should therefore be subject to less stringent regulations than agents who open accounts and process loans. Since cash merchants do not provide services such as account opening and customer enrollment, they are more easily shared among different mobile financial services providers.

11. Electronic funds transfer (EFT): Any transfer of funds initiated through an electronic terminal, telephone, computer, or magnetic tape for the purpose of ordering, instructing, or authorizing a financial institution to debit or credit a consumer’s bank or e-money account.

12. Electronic money (e-money): A type of monetary value electronically recorded and generally understood to have the following attributes:

· Issued upon receipt of funds in an amount no lesser in value than the value of the e-money issued;

· Stored on an electronic device (e.g. a chip, prepaid card, mobile phone, or computer system);

· Accepted as a means of payment by parties other than the issuer; and

· Convertible into cash.

Regulators often consider interest payments to be a feature unique to deposits. Consequently, when e-money is considered a payment service (and not deposit-taking), the payment of interest is prohibited.

13. Electronic payment (e-payment): Any payment made with an electronic funds transfer (EFT).

14. Float: The total outstanding amount of e-money issued by an e-money issuer. Customer funds backing a float should be subject to fund safeguarding and fund isolation measures.

For e-money, Fund isolation, together with fund safeguarding, constitutes the primary means of protecting customer funds in a nonbank-based model. Fund isolation: Measures aimed at isolating customer funds (i.e. funds received against equal value of e-money) from other funds that may be claimed by the issuer or the issuer’s creditors. Fund safeguarding: Measures aimed at ensuring that funds are available to meet customer demand for cashing out electronic value. Such measures typically include: (i) restrictions on the use of such funds; (ii) requirements that such funds be placed in their entirety in bank accounts or government debt; and (iii) diversification of floats across several financial institutions. Why is fund safeguarding important? Fund safeguarding, together with fund isolation, protects customer funds in a nonbank-based model.

15. G2P: Government-to-person payment. G2P payments include government benefits and salary payments.

16. Inter-connectivity: The ability to enable a technical connection between two or more schemes or business models, such as a bank or payment services provider to an international or regional payment network. Interconnectivity with a payment scheme (e.g. Visa or Mastercard) requires a bank to go through a certification process.

17. Interoperability: Payment instruments belonging to a particular scheme or business model that are used in other systems and installed by other schemes. Interoperability requires technical compatibility between systems, but can only take effect when commercial interconnectivity agreements have been concluded.

18. Know Your Agent (KYA) or Agent due diligence: Measures taken by a mobile financial services provider to assess potential agents and their ability to carry out agent functions related to mobile financial services. Why is KYA important? Because agents are often exempt from regulatory or other transaction limits in order to provide service to more customers, greater due diligence is required of agents than customers.

19. Know Your Customer (KYC): A set of due diligence measures undertaken by a financial institution, including policies and procedures, to identify a customer and the motivations behind his or her financial activities. KYC is a key component of AML/CFT regimes. Why is KYC important? FATF Recommendation 10 requires identification of the customer and verification of identification, but since identification is not always available to poor customers, this can be a hindrance to financial inclusion. Banks often apply additional KYC requirements beyond those required by international FATF standards. Alternatively, Customer due diligence (CDD) are measures, but generally refers more broadly to a financial institution’s policies and procedures for obtaining customer information and assessing the value of the information for detecting, monitoring, and reporting suspicious activities. Banks conduct CDD as part of due diligence separate from anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) concerns. Bank CDD measures are often more comprehensive than the KYC measures required by law.

20. Mobile banking (m-banking): The use of a mobile phone to access banking services and execute financial transactions. This covers both transactional and non-transactional services, such as viewing financial information on a bank customer’s mobile phone.

21. Mobile financial services (MFS): The use of a mobile phone to access financial services and execute financial transactions. This includes both transactional and non-transactional services, such as viewing financial information on a user’s mobile phone. Mobile financial services include both mobile banking (m-banking) and mobile payments (m-payments).

22. Mobile network operator (MNO) / Telco: A company that has a government-issued license to provide telecommunications services through mobile devices. An MNO is sometimes known as a mobile phone operator or wireless service provider. MNOs are important due to their experience with high-volume, low-value transactions and large networks of airtime distributors have made.

23. Nonbank-based model: A mobile financial services business model (bank-led or nonbank-led) in which (i) the customer has a contractual relationship with a nonbank financial service provider and (ii) the nonbank is licensed or otherwise permitted by the regulator to provide the financial service(s).

24. Nonbank-led model: A mobile financial services business model (bank-based or nonbank-based) in which the nonbank is the primary driver of the product or service, typically taking the lead in marketing, branding, and managing the customer relationship.

25. P2B: Person-to-business payment. P2B payments include payments for the purchase of goods and services.

26. P2G: Person-to-government payment. P2G payments include taxes and fees.

27. P2P: Person-to-person payment. P2P payments include both domestic and international remittances.

28. Payment service provider (PSP): An entity providing services that enable funds to be deposited into an account and withdrawn from an account; payment transactions (transfer of funds between, into, or from accounts); issuance and/or acquisition of payment instruments that enable the user to transfer funds (e.g. checks, e-money, credit cards, and debit cards); and money remittances and other services central to the transfer of money.

29. Risk-based approach: A method for complying with AML/CFT standards set forth in FATF Recommendation 1. The risk-based approach is based on the general principle that where there are higher risks, countries should require financial services providers to take enhanced measures to manage and mitigate those risks. Where risks are lower (i.e. no suspicion of money laundering or terrorist financing), simplified measures may be allowed. Why is a risk-based approach important? A risk-based approach can often promote greater financial inclusion. A risk-based approach is appropriate for countries that want to build a more inclusive financial system that brings the financially excluded (who may present a lower risk of money laundering/terrorist financing) into the formal financial sector. It is broadly recognized that this approach requires significant domestic consultation and cross-sector dialogue.

30. Third-party provider: Agents and others acting on behalf of a mobile financial services provider, whether pursuant to a services agreement, joint venture agreement, or other contractual arrangement. Mobile financial services providers should be liable for the actions of third-party providers acting on their behalf regardless of the third parties’ legal status (agent or not).

Introduction:

The world is on the move like never before. According to a recent World Bank study, 75% of the world has access to mobile phones. According to Wikipedia, Bangladesh ranked number 10 in usage of mobile phone with its 120,393,000 users by way of 75.2 connections per 100 citizens, as evaluated in December 2014 (Wikipedia, 2015), however, the active unique subscriber base is roughly 70 million, as mentioned by BTRC (BTRC, 2014). In urban areas, mobile penetration has reached almost 100% and the continued growth is coming from semi-urban and rural areas, driven by cheap handsets, cheap connections and one of the lowest voice call charges in the world. Mobile has brought about a silent revolution in a country in the course of 50% still do not have access to electricity. Mobile revolution touches almost every sector including financial services amid 19 out of 28 banks started MFS operation in Bangladesh with its 25 million registered customers and 541 thousand countrywide agents. It’s easy to understand why this is top of mind for consumers, businesses and banks (Bangladesh Bank, 2015). MFS, which has the potential to radically transform how money is managed, provide incredible convenience and excellent customer service opportunities amid customers have their mobile devices with them virtually all the time and no other channel can provide the same level of ready access to accounts. However, in the rush to meet consumer demand and create market differentiation, fraud controls were too often an afterthought, as (41STParameter, 2013) observes. According to a recent survey by Aite Group9, 88 % of global risk executives at financial institutions believe mobile is the next big point of exposure. The speed-to-market imperative has so sometimes overshadowed and outpaced the deployment of fraud prevention technologies capable. This paper attempted to examine the potential risks along with to develop strategies in minimizing those risks while still recognizing the business and operational value of MFS in Bangladesh.

1.1. Objectives:

The primary objective of this report is to portrait the Mobile Financial Services that are used by the criminals to commit various typical crimes as well as some mobile phone related crime for which, victims of these crimes hanker after immediate attention from and relief by the law enforcers. LEA, who are expected to assist the victims and also to bring the law breakers to book therefore, must be provided a clear understanding on this new system that are rapidly developing and frequently changing; plus should be supported without delay with necessary legal, material and training infra-structure. Other major objectives are listed below:

1.2. Methodology:

This report is based mainly on literature study, case studies and analysis of the issues. Both the primary as well as the secondary form of information has been used to prepare the report. They were collected from sources which have been:

1.2.1. Primary sources:

1.2.2. Secondary source:

In spite of sincere efforts to reduce any probable short-comings, it is felt that a couple of workshops in participations with various stakeholders would be great to fine-tune the outcome of this paper.

2. Mobile Financial Services in Bangladesh: Legal infra-structure

2.1. What is Mobile Financial Services?

The term mobile financial service refers to any of a series of personal finance or banking related actions that an individual can engage in using a mobile phone. Any phone is a potential MFS terminal. The systems run via universal phone protocols (like SMS and USSD), applications installed on the SIM card (SIM Toolkit), or applications installed on the handset itself. MFS is not reliant on internet connectivity for its operation, enabling its usage on a range of handsets.

As it is defined by Bangladesh Bank, (Bangladesh Bank 2012) Mobile Financial Services (MFS) is an approach to offering financial services that combines banking with mobile wireless networks which enables users to execute banking transactions. This means the ability to make deposits, withdraw, and to send or receive funds from a mobile account. Often these services are enabled by the use of bank agents that allow mobile account holders to transact at independent agent locations outside of bank branches.

2.2. MFS in Bangladesh: Legal infra-structure

2.2.1. Bangladesh Bank allows various types of Mobile Financial Services like a. Disbursement of inward foreign remittances; b. Cash in /out using mobile account through agents/Bank branches/ ATMs/Mobile Operator’s outlets (P2P) ; c. Person to Business Payments (P2B) ‐ e.g. utility bill payments, merchant payments; d. Business to Person Payments (B2P) e.g. salary disbursement, dividend and refund warrant payments, vendor payments, etc. e. Government to Person (G2P) Payments e.g. elderly allowances. Freedom‐fighter allowances, subsidies, etc. f. Person to Government Payments (P2G) e.g. tax, levy payments; g. Person to Person Payments - One registered mobile Account to another registered mobile account; h. Other payments like microfinance, overdrawn facility, insurance premium, DPS etc. (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, p-1).

2.2.2.Approval from Bangladesh Bank is mandatory prior to go for business with Mobile Financial Services. The Cash Points/Agents shall have to be selected by the respective bank and a list of the Cash Points/ Agents with their names and addresses shall have to be submitted to the Department of Currency Management and Payment System (DCMPS), Bangladesh Bank and will be updated on monthly basis. As per regulations, at any point of time, the relevant balance in bank book shall be equal to the virtual balance of all registered mobile accounts shown in the system. Banks will be the custodian of individual customers' deposits and ‘Bangladesh Bank may withhold, suspend or cancel approval for providing MFS services if it considers any action by any of the parties involved in the system detrimental to the public interest’ (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 7.1, p-2).

2.2.3.Depending on the operation, responsibility and relationship(s) among banks, MNOs, Solution Providers and customers, mainly two types of mobile financial services (Bank led and Non Bank led) are followed worldwide. But from legal and regulatory perspective, the central bank only allows the bank‐led model in Bangladesh (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 6.0, p-2).

The bank‐led model shall offer an alternative to conventional branch‐based banking to unbanked population through appointed agents facilitated by the MNOs/Solution Providers. It may be mentioned that Customer account, termed "Mobile Account" will rest with the bank and will be accessible through customers’ mobile device. Such Mobile Account will be a non‐chequing limited purpose account.

3. How Does MFS Work?

3.1 .Opening an MFS account:

3.1.1. As per regulations, respective bank ‘shall have to use’ a 'Know Your Customer (KYC)' format and will be responsible for authenticity of the KYC of all the customers (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 9.0, p-3). We articulate here the working format of Bkash – a subsidiary institution of Brac Bank. To open a bkash Wallet meaning mobile account with bkash (bkash, 2015), you need to go to any of your nearby bkash Agent along with -

a. Your mobile phone with Grameenphone, Banglalink, Robi, or Airtel connection

b. A copy of your Photo ID (National ID/Passport/Driving License)

c. 2 copies of Passport size photographs’.

As bkash website describes, ‘You are to fill out the Wallet Opening Form and put your thumb print and signature properly’.

3.1.2. So, during investigation of any suspicious false registration, if agent is found to process the registration on behalf of the bank, agent must satisfy an enquiry officer:

a. That the person whose photo was used in the KYC, himself or herself signed on the form [unlike a 29 years came with a photo of 62 years and signed with no objection from agent’s side is clearly violation of the existing law]

b. That the original ID was shown to agent during submission of a photo-copied one [in most fake registration cases, there had never been any ‘original’ ID other than a computer produced ‘photo-copied’ one]

c. That agent had taken sufficient precautionary measures in case of an account holder using same (not similar) photograph both in ID and in KYC [Use of same photograph both in national ID and KYC is almost impossible other than an adulterated ones]

3.1.3. During defining agents’ role in opening an account fraudulently, we also mustn’t forget that it’s bank’s responsibility for authenticity of the KYC data all through initiating a mobile bank account (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 9.0, p-3).

3.2 How transaction made through MFS

After registration, the initial action of MFS consumers is to load value (e-money) into their accounts. To accomplish this, the user buys (cash-in) e-money from an agent affiliated with their MFS. This transaction can differ in its details, but in general there is a requirement that the consumer present valid ID and sign the agent’s logbook. If the user then wishes to make a P2P transfer, they enter the recipient’s MFS account number. Both sender and receiver will then receive an SMS confirmation of the transaction. The receiver is then able to cash out the e-money, minus the transaction fee. To do this they go to an agent or ATM, present ID and follow the MFS’s directions on how to transfer e-money from the user’s account to the agent’s. This basic model can differ slightly for P2B and P2G, though the initial “load-in” method is the same. Large scale B2P and G2P payments have different load-in procedures, but recipient cash-out and/or transfers in the system are the same as the basic P2P model.

Look at the diagrams of a Cash-in of Tk. 3,000 to any MFS account 01xxxxxxxxx and a cash-out of Tk. 3,000 from the same below:

Please note that a client is to be charged some transaction fee for each cash-out, while agent can’t charge a client for cash-in. Hence, any fee charge during cash-in by agent is illegal.

An investigator has any or all of the following areas to look for evidence of transactions - of both cash-in and cash-out:

a. Statement of MFS bank.

b. Transaction log register maintained by Agents.

If agents fail to produce transaction log register, or if the respective column is not signed by the owner of MFS account, this will imply agents’ bad intention to hide names or identities of persons dealing with money causing money laundering offence.

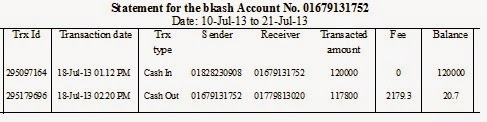

Case Study 3.2: Unknown member of CNG-theft group asked the owner (victim) of the vehicle over phone to ‘bkash’ Tk. 170,000 to 01679131752. Victim went to a local MFS agent of his area and told him that he wanted to ‘bkash’ Tk. 170,000.

What the agent should do now?

a. ‘Do you have any MFS account? No? O, it’s easy to open an account. Bring a copy of passport size photograph along with your mobile phone and national ID card. I will open a MFS account right now – free!’

b. [After opening account, receiving money from him and doing cash-in back to his new account] ‘You’ve e-money now. Send your money yourself wherever you want.’ [This is what we have been watching in TV advertisement; the viewers are never been told that sending money without opening an account is a punishable offence, what we have been wrongly educated that opening an account for sending money is just only a smarter and better alternative.]

c. ‘Sorry, you can’t send Tk. 170,000 in a day. The maximum approved amount is Tk. 25,000 a day; even to use multiple accounts for sending more than Tk. 25,000 is not allowed.’

Nonetheless, see, what the agent-in-this-case (say, agent ‘A’) has done:

a. ‘Give me money plus service charge’ (and the service charge is illegal – no money can be charged for cash-in)

b. Agent A then ‘cash-in’ from his ‘agent account’ to personal account of the suspect – (actually in this case and in most cases) the personal account of the suspect’s local Bkash agent (say Agent ‘B’).

c. Agent B received e-money to his ‘own personal account’, then got money cashed out to his ‘agent account’ and lastly gave money to known or unknown suspect. An amount of Tk. 170,000 has been ‘sent’! This is a case of July’13, however, a latest circular issued by Bangladesh Bank restrict maximum limit of cash-in a day Tk. 25,0000. (Bangladesh Bank, 2013).

d. Agent B also failed to maintain any valid transaction log, because the person who received money didn’t sign here.

e. Even if he signed, it would be illegal, as ‘money receiver’ is not really ‘account owner’ here; a known or unknown suspect or criminal simply received ‘crime proceeds’ through a personal account maintained by the agent B, however, a BFIU circular order, allows to send money without KYC a maximum amount of Tk. 1,000 a day (BFIU, 2012, p-3, Sec. Gha-7). Nonetheless, the agent thus engages himself into a ‘predicate offence’, simultaneously also engaging himself in ‘money laundering’.

Here is now, Comparative Money Flow Charts to show how an MFS is to work, but how it is working in Bangladesh in the course of committing crime and assisting crime.

Figure 3.2.4a. How MFS is to work versus how it’s working

|

Again, let us work with the transaction of our case study 3.2. Can we develop a Money Flow Chart based on the bank statement?

Agent Assist Crime

|

Figure 3.2: How agents assist crime through direct ‘cash-in’ into recipient’s account

If you look into in the Money Flow Chart developed from the bank statement, you will see, a zero length m-loop transaction (we will discuss about m-loop in paragraph 3.5) facilitates here to occur a crime – a predicate offense. A layman definition of ‘zero-length m-loop transaction’ may be expressed as ‘a transaction without any formal transaction’ (causing money laundering in most cases). In the above case study, on the record:

a. The account holder of 01679131752 (the suspect or agent B) first cash-in and by the couple of hours then cash-out causing to lose several thousand Taka.

b. He was into the premise of agent A to load (cash-in) e-money.

However, it is evident and is possible to prove that the loader (agent A) and the loaded account (agent B) were in two different places; and so, the loaded account holder (either it’s suspect or its crime-partner agent) didn’t sign into transaction log register of agent A.

c. During cash-out e-money (which is always done readily, without delay; it is evident what makes them to do hurry!) from his own personal account to agent account (agent B), this is not the real recipient, who sign (in case, you found it to be signed) into transaction log register; nonetheless, he is NOT the account holder of that account!

Now what the MFS agent need to satisfy an investigator in the above case:

a. That Agent A got the owner of 1679131752 (agent B) to sign into transaction-log register (he can’t and didn’t do it really);

b. That Agent B received the said amount of e-money into his personal account, because he deposited said amount of money to agent A; unless he show that he discovered some money from a suspicious source and as an MFS agent, he informed the central bank officially about such suspicious transaction in prescribed format without delay;

c. That Agent B cashed-out…. so on . You can add a number of arguments if you study the standard rules set by the central bank or agents’ own authority, not to say about the law of the land.

3.3. Transaction Limit , STR and SAR in MFS:

3.3.1. Bangladesh Bank fixes the transaction limit as well as overall cap (per customer/ per month) for Person to Person Payments as and when needed. These limits are not applicable for P2B, B2P, P2G, G2P transfers. An agent is allowed to cash-in maximum 5 times daily into his personal account. Any customer is allowed to cash-in maximum 5 times a day, but 20 times a month; cash-out maximum 3 times a day, but 10 times a month using his personal account. Again any customer is allowed to cash-in and cash-out maximum Tk. 25,000 a day, but Tk. 150,000 a month; and for P2P transfer, maximum Tk. 10,000 a day, but Tk. 25,000 a month.

3.3.2. We will however, see later that these limits along with many other mandatory provisions are vehemently non-complied using innumerable accounts mostly by the agents themselves. In spite of the directions given by the central bank as well as of its own employer on MFS transaction process, we’ll see how MFS agent avoided the central banks’ instruction on maximum limits (Tk. 25,000) in sending money. It is an offence of money laundering done by both the MFS agent. Agents also engaged into a predicate offence – fraud/extortion (mostly) with false promising of thieves to return victim’s stolen vehicle.

Lack of effective monitoring by the controlling authority as well as absence of LEA representative in the monitoring mechanism widely facilitate the key players to bypass or not to comply the existing rules, regulations and laws. Persons who hardly care about compliance of law almost face no problem from the monitoring authority as well as from the LEA, who barely had representation in the monitoring body unlike many part of the world.

3.3.3. Banks shall also to ‘ensure that suspect transactions can be isolated for subsequent investigation and are to ‘develop an IT based automated system to identify suspicious activity/transaction report (STR/SAR) before introducing the services, and also are to immediately report to Anti‐Money Laundering Department of Bangladesh Bank regarding any suspicious, unusual or doubtful transactions likely to be related to money laundering or terrorist financing activities. Banks are also to report to Bangladesh Bank in several formats including the following format for Bangladesh Bank oversight (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 9.0, p-3).

Annex V

| ||||||||

Monthly Report of Person to Person Mobile Financial Transactions

| ||||||||

Name of the Bank :

Date :

| ||||||||

(Tk. 20,000 and above)

| ||||||||

Sl.

No

|

Mobile

Account No of the Sender

|

Name of

the

Sender

|

Source of

Income of

the

Sender

|

Relationship

with recipient

|

Mobile

Account

No. of the

Receiver

|

Name of

the

Receiver

|

Purpose of

the

transaction

|

Amount

Transferred

|

1

| ||||||||

2

| ||||||||

N.B. : Transaction amount less than Tk. 20,000 shall have to be reported on consolidated basis mentioning total number and amount.

3.3.4. As per regulations, MFS transaction‐records must be retained for six (06) years from the origination date of the entry. The Participating Bank(s) must, if requested by its customer, or the Receiving Bank(s), provide the requester with a printout or reproduction of the information relating to the transaction. Banks should also be capable of reproducing the MFS transaction‐records for later reference, whether by transmission, printing, or otherwise.

3.4. Know Your Agent(KYA) or Agent due diligence:

Regulation of the central bank has given responsibility to the banks to identify, contract, educate, equip and monitor activities of the agents on a regular basis. It wants a clear, well documented Agent Selection Policy and Procedures by the bank, where the later are to publish list as well as addresses of cash points/agents/partners in their website. Central bank wants the following issues should be taken into account for selection of partners/agents (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 8.0, p-3):

1. Competence to implement and support the proposed activity;

2. Financial soundness;

3. Ability to meet commitments under adverse conditions;

4. Business reputation;

5. Security and internal control, audit coverage, reporting and monitoring environment;

Before we discuss ‘Money laundering’ we like to talk on zero-length m-loop and we will also discuss what the respective financial institution also could do by taking measures and also by reporting these transactions as STR to the central bank.

3.5. What is an m-loop?

To transact money,

a. An MFS account holder ‘A’ first buys (cash-in) e-money from an agent, of course fulfilling the requirement by presenting valid ID and signing into the agent’s logbook.

b. To make a P2P transfer, he then uses his own mobile phone to enter the recipient’s (say, ‘B’) MFS account number; and both sender and receiver will then receive an SMS confirmation of the transaction.

c. The receiver B is then able to cash out the e-money, minus the transaction fee. To do this he goes to an agent (or ATM) for cash-out, again by presenting ID and following the MFS’s directions on how to transfer e-money from the user’s account to the agent’s.

Here there occurs 1(one) transaction from user A to B. Hence, it’s an m-loop with length 1, where remittance is done once only. That is, one account remitting to another is making one loop and making only one transaction. But when four accounts are involved and one is remitting to three accounts, then the process gets lengthier in lower cost for both parties.

Look at the diagram of the left side shown below:

Lengthening E-money loop

|

Length=1; Remittance made is only 1

Length=3; Remittance made is 3

What is length of m-loop of our Case Study 3.2. that we discussed above?

Statement of a bKash Account

|

The official version of the statement is: the account holder 01679131752 was in a hurry to mislay Tk. 2,179.30 by a couple of hours through a zero-length transaction.

You see here a zero-length money-loop transaction, where no formal transaction is done. Officially, the user of cash-in money, hurriedly cashed out for no reason and arranged to drop some money. Here responsibility lies with the financial institution to report about this very charitable transaction as STR to the central bank. Such rapid transactions that officially benefit the bank, the distributor and the agent only, not the customer, must be reported to the central bank to obey the existing law of the land.

Moreover, money-loops of higher lengths shows:

a. the mobility of mobile financial system, the positive strength of MFS,

b. allows MFS institution to keep physical money for longer time; i.e. allows to work as a banking institution more effectively.

On the contrary, zero or one length money transaction is the sign of poor health of MFS institutions that merely works as a courier service, of course, in most cases produces a huge amount of money laundering occurrences by hiding the real players of transaction every day.

What is the case of Bangladesh MFS market? Is it zero, one or more than one which tops? How zero-length transaction causes money laundering? Let us see first, what is money laundering as per the existing law of the land?

3.6. What is money laundering?

In lay terms Money Laundering is most often described as the “turning of dirty or black money into clean or white money”. If undertaken successfully, money laundering allows criminals to legitimize "dirty" money by mingling it with "clean" money, ultimately providing a legitimate cover for the source of their income. Generally, the act of conversion and concealment is considered crucial to the laundering process. A definition of what constitutes the offence of money laundering under Bangladesh law is set out in Section 2 (Tha) of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2012, which is reads as follows:

“ (i) Knowingly moving, converting, or transferring proceeds of crime or property involved in an offence for the following purposes:-

(2) assisting any person involved in the commission of the predicate offence to evade the legal consequences of such offence;

(ii) smuggling money or property earned through legal or illegal means

to a foreign country ;

(iii) knowingly transfer ring or remitting the proceeds of crime to a foreign country or remitting or bringing them into Bangladesh from a foreign country with the intention of hiding or disguising its illegal source; or

(iv) concluding or attempting to conclude financial transactions in such a manner so as to reporting requirement under this Act may be avoided;

(v) converting or moving or transferring property with the intention to instigate or assist for committing a predicate offence;

(vi) acquiring, possessing or using any property, knowing that such property is the proceeds of a predicate offence;

(vii) performing such activities so as to the illegal source of the proceeds of crime may be concealed or disguised;

(viii) participating in, associating with, conspiring, attempting, abetting, instigate or counsel to commit any offences mentioned above;”

We can see, the working format of MFS agent along with the member of CNG theft group mentioned in our case study 3.2 clearly violates the italic part of the definition, by (1)concealing or disguising the illicit nature, source, ownership or control of the proceeds of crime; (2) assisting a member of theft group involved in the commission of the predicate offence to evade the legal consequences of such offence; and also (3) concluding or attempting to conclude financial transactions in such a manner so as to reporting requirement under this Act may be avoided.

3.7. Look into the Comparative Summary Statement on MFS in Bangladesh prepared by using information provided by Bangladesh Bank. What do you see?

Comparative summary statement on MFS in Bangladesh

(for the period from October, 2014 to December, 2014)

In a standard situation cash-out is followed by P2P and B2P transaction; hence, for a particular period, the number of cash-outs should not exceed total number of P2P and B2P. For 3 months’ records, we see total cash-out transaction: Tk.10,534.68 Crore; whereas during same period, total P2P, B2P including other transaction: Tk. 5,794.10 Crore. Considering Cash-in amount Tk. 11,844.79 Crore , can we derive the total money with zero-length m-loop as Tk. 4,740.58 Crore Tk.? This shows more than Tk. 18 Thousand Crore a year is transacted keeping no records of actual senders or recipients. All these could be subject to STR to the central bank by hiding the real players of transaction every day.

3. Money Laundering in MFS: perspective Bangladesh

4.1. Why Money Laundering is done?

Criminals engage in money laundering for three main reasons:

a. Money represents the lifeblood of the organization that engages in criminal conduct for financial gain because it covers operating expenses, replenishes inventories, purchases the services of corrupt officials to escape detection and further the interests of the illegal enterprise, and pays for an extravagant lifestyle. To spend money in these ways, criminals must make the money they derived illegally appear legitimate.

b. A trail of money from an offense to criminals can become incriminating evidence. Criminals must obscure or hide the source of their wealth or alternatively disguise ownership or control to ensure that illicit proceeds are not used to prosecute them.

c. The proceeds from crime often become the target of investigation and seizure. To shield ill-gotten gains from suspicion and protect them from seizure, criminals must conceal their existence or, alternatively, make them look legitimate.

4.2. Why we must combat Money Laundering

a. Money laundering has potentially devastating economic, security, and social consequences.

Money laundering is a process vital to making crime worthwhile. It provides the fuel for drug dealers, smugglers, terrorists, illegal arms dealers, corrupt public officials, and others to operate and expand their criminal enterprises. This drives up the cost of government due to the need for increased law enforcement and health care expenditures (for example, for treatment of drug addicts) to combat the serious consequences that result. Crime has become increasingly international in scope, and the financial aspects of crime have become more complex due to rapid advances in technology and the globalization of the financial services industry.

b. Money laundering diminishes government tax revenue and therefore indirectly harms honest taxpayers. It also makes government tax collection more difficult. This loss of revenue generally means higher tax rates than would normally be the case if the untaxed proceeds of crime were legitimate. We also pay more taxes for public works expenditures inflated by corruption. And those of us who pay taxes pay more because of those who evade taxes. So we all experience higher costs of living than we would if financial crime - including money laundering—were prevented.

c. Money laundering distorts asset and commodity prices and leads to misallocation of resources. For financial institutions it can lead to an unstable liability base and to unsound asset structures thereby creating risks of monetary instability and even systemic crises. The loss of credibility and investor confidence that such crises can bring has the potential of destabilizing financial systems, particularly in smaller economies.

d. One of the most serious microeconomic effects of money laundering is felt in the private sector. Money launderers often use front companies, which co-mingle the proceeds of illicit activity with legitimate funds, to hide the ill-gotten gains. These front companies have access to substantial illicit funds, allowing them to subsidize front company products and services at levels well below market rates. This makes it difficult, if not impossible, for legitimate business to compete against front companies with subsidized funding, a situation that can result in the crowding out of private sector business by criminal organizations.

e. No one knows exactly how much "dirty" money flows through the world's financial system every year, but the amounts involved are undoubtedly huge. The International Money Fund has estimated that the magnitude of money laundering is between 2 and 5 percent of world gross domestic product, or at least USD 800 billion to USD1.5 trillion. In some countries, these illicit proceeds dwarf government budgets, resulting in a loss of control of economic policy by governments. Indeed, in some cases, the sheer magnitude of the accumulated asset base of laundered proceeds can be used to corner markets -- or even small economies.

f. Among its other negative socioeconomic effects, money laundering transfers economic power from the market, government, and citizens to criminals. Furthermore, the sheer magnitude of the economic power that accrues to criminals from money laundering has a corrupting effect on all elements of society.

g. The social and political costs of laundered money are also serious as laundered money may be used to corrupt national institutions. Bribing of officials and governments undermines the moral fabric in society, and, by weakening collective ethical standards, corrupts our democratic institutions. When money laundering goes unchecked, it encourages the underlying criminal activity from which such money is generated.

h. Nations cannot afford to have their reputations and financial institutions tarnished by an association with money laundering, especially in today's global economy. Money laundering erodes confidence in financial institutions and the underlying criminal activity -- fraud, counterfeiting, narcotics trafficking, and corruption -- weaken the reputation and standing of any financial institution. Actions by banks to prevent money laundering are not only a regulatory requirement, but also an act of self- interest. A bank tainted by money laundering accusations from regulators, law enforcement agencies, or the press risk likely prosecution, the loss of their good market reputation, and damaging the reputation of the country. It is very difficult and requires significant resources to rectify a problem that could be prevented with proper anti-money-laundering controls.

i. It is generally recognized that effective efforts to combat money laundering cannot be carried out without the co-operation of financial institutions, their supervisory authorities and the law enforcement agencies. Accordingly, in order to address the concerns and obligations of these three parties, respective Guidance Notes should be drawn up.

4.3. Stages of Money Laundering

a. There is no single method of laundering money. Methods can range from the purchase and resale of a luxury item (e.g. a house, car or jewellery) to passing money through a complex international web of legitimate businesses and 'shell' companies (i.e. those companies that primarily exist only as named legal entities without any trading or business activities). There are a number of crimes where the initial proceeds usually take the form of cash that needs to enter the financial system by some means. Bribery, extortion, robbery and street level purchases of drugs are almost always made with cash. This has a need to enter the financial system by some means so that it can be converted into a form which can be more easily transformed, concealed or transported. The methods of achieving this are limited only by the ingenuity of the launderer and these methods have become increasingly sophisticated.

b. Despite the variety of methods employed, the laundering is not a single act but a process accomplished in 3 basic stages which may comprise numerous transactions by the launderers that could alert a financial institution to criminal activity -

Placement - the physical disposal of the initial proceeds derived from illegal activity.

Layering - separating illicit proceeds from their source by creating complex layers of financial transactions designed to disguise the audit trail and provide anonymity.

Integration - the provision of apparent legitimacy to wealth derived criminally. If the layering process has succeeded, integration schemes place the laundered proceeds back into the economy in such a way that they re-enter the financial system appearing as normal business funds.

c. The three basic steps may occur as separate and distinct phases. They may also occur simultaneously or, more commonly, may overlap. How the basic steps are used depends on the available laundering mechanisms and the requirements of the criminal organisations. The table below provides some typical examples.

Placement stage

|

Layering stage

|

Integration stage

|

Cash paid into bank

(sometimes with staff

complicity or mixed with

proceeds of legitimate

business).

Cash exported.

Cash used to buy high value

goods, property or business

assets.

Cash purchase of single

premium life insurance or other

investment.

|

Sale or switch to other forms of investment.

Money transferred to assets of

legitimate financial

institutions.

Telegraphic transfers (often

using fictitious names or funds

disguised as proceeds of

legitimate business).

Cash deposited in outstation

branches and even overseas

banking system.

Resale of goods/assets.

|

Redemption of contract or

switch to other forms of

investment.

False loan repayments or

forged invoices used as

cover for laundered

money.

Complex web of transfers

(both domestic and

international) makes

tracing original source of

funds virtually impossible

|

Banks and its partners shall have to comply with the prevailing Anti‐Money Laundering (AML)/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) related laws, regulations and guidelines issued by Bangladesh Bank from time to time (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 9.0, p-3). Banks are also responsible for mitigation of all kinds of risks such as liquidity risk, operational risks, fraud risks including money laundering and terrorist financing risks. Technical risks should be covered by the solution provider. As per regulations the banks bear all the liabilities that arise from improper action on the part of their subsidiaries/cash points/ agents/ partners.

5. Evaluating usages, opportunities and vulnerabilities in MFS

5.1. Usages of MFS:

Mobile payment

Mobile remittance

Mobile banking

Mobile payments can be used for the following three types of transactions (Consumers International, 2014):

1. Mobile payment – Paying for goods and services: shopping, paying bills, etc.

2. Mobile remittance - Sending money to or receiving from an individual, person-to-person, intra- or inter-national.

3. Mobile banking- Withdrawals, transfers and other transactions on actual bank accounts.

5.2. Opportunities:

Consumers’ security

Traceability

Increased revenues

Reduced corruption

Mobile finance is widely lauded as a development tool. Proponents extol the financial benefits to users, whether it be through the low-cost transfer of funds, the saved opportunity costs when a user makes a mobile payment rather than going into town, or in some cases the ability to access more traditional financial instruments, such as bank accounts and micro-loans. Somewhat less frequently, the proponents cite the benefits of the systems’ safety and security. The research (STATT, 2012) indicates that mobile finance brings a broad range of benefits to users and law enforcement agencies.

Firstly, the storage of value in an MFS lessens users’ vulnerability to theft and other financially motivated crimes.

Secondly, every transaction conducted via MFSs generates electronic records, creating investigative and evidentiary opportunities.

Thirdly, a shift of P2G payments from cash to mobile can boost revenue collection while reducing opportunities for petty corruption.

Table 5.1: Security opportunities and vulnerabilities in MFS

Opportunities

|

Vulnerabilities

|

Increased consumer security

|

Money laundering

|

Improved traceability along with reduction in common crime

|

Assistance in traditional crime

|

Increased Government revenues

|

Enabling new crimes

|

Reduced corruption

| |

Innovative business exploration

|

5.3. Vulnerabilities

Money laundering

Assisted plus Enabled Crime

5.3.1. Money Laundering

5.3.1.1. Money laundering is mostly done through mobile accounts registered with fake identity. An investigator (CID, 2014) from CID, Bangladesh Police, observed that: ‘While we ask for KYC information during investigation of any relevant crime, 99 out of 100 KYCs are turned out to be with false registration. Of course, if criminals have easy opportunity to open mobile account in fake names, why they will open account exposing their real names?’ Agents simply ignore maintaining minimum CDD during opening an account, nonetheless, Bangladesh law authorize only dealing banks to open a new account. We will also see later that in many cases, agents themselves are actively involved in various kinds of active criminal activities including collecting ransom money by human trafficking, extortion, fraud by maintaining several hundred false or real accounts by themselves.

5.3.1.2. So, the second and perhaps more preventable problem involves agents’ due diligence. Agents hardly follow ID requirements. Denials of service occurred in Bangladesh perhaps on less than 1% of occasions when a customer lacks ID. Agents’ motivations for failing to implement due diligence procedures are mostly because of ‘due diligence in implementing the existing law’. Agents are not banks’ employees; they are mostly quasi-literate, untrained and rarely sensitized formally or informally.

Agents being quasi-independent operators in the business, find no problems breaking laws regularly in order to make money. Their interest is in processing as many transactions as possible. As well, this is again the problem with LEA, who fails to communicate the message to the community that money laundering is a serious issue that needs to be complied by everyone. As it is observed (STATT, 2012): The respective banks have grown their agent-networks so rapidly that the number of agents would challenge any regulatory regime. As stated by one researcher, if you are an agent “you can do as you want, as long as no one reports you and the person above you doesn't get angry with you.

Case Study 5.3.1.2. A TV advertisement of a reputed MFS shows that an ‘educated young man’ was talking to her mother that he was unable to send money, because there was no ‘bkash account’ near to him. He was readily advised by a lady co-passenger to open his own account being ‘an educated man’. The advertisement simply failed to give message to its viewers that ‘sending money by some-one’s else account is just a criminal offence’. It is not an issue of prestige of an ‘educated man’ rather is a mandatory requirement, non-compliance of which is plainly punishable by the law of the land. Thus, even media campaigns by banks hardly try to educate its stakeholders with genuine information, which is of course inconsistent with the instructions of the central bank, where it says, ‘Banks shall take appropriate measures (may issue proper guidelines for dealing with customer service and customer education) to raise awareness and educate their customers and employees for using Mobile Financial Services (Bangladesh Bank, 2011, section 12.0, p-4).

5.3.1.3. A related yet distinct challenge to KYC or CDD is the increasing use of ATMs as output devices. Strongly favored by consumers for both convenience and liquidity issues, ATM withdrawal’s system does not require ID at the point of withdrawal.

5.3.1.4. Apart from ID challenges, the possession of multiple accounts by individual consumers undermines the AML potential of transaction limits. One interview subject reported, as observed by (STATT, 2012): I’ve met several businessmen who had multiple phones, multiple accounts. They’d just sit there and transact on one phone until they hit the maximum [daily limit] and then move on to their other accounts.

Maximum 2 accounts can be maintained by one. If any agent fails to maintain such conditions, this is not clear what measures are being taken by bank authority or by the regulatory body apart from taking legal measures under Anti-Money laundering Act 2012 by the LEA.

5.3.1.5. MFS are far more likely to be used for payments within structured criminal groups. Regular, intra-group payments would probably not be affected by transaction limits, nor would they necessarily be flagged by the mobile finance product’s e-monitoring systems. MFS could be of particular use to large organizations that operate in geographically disparate regions within a country, such as large ethnically organized criminal groups, drug traffickers and poachers/smugglers in wildlife. A journalist interviewed by STATT in Nairobi alluded to this, noting that some payments for ivory smuggling were done via MFS. Such transactions are functionally more akin to terrorist finance, in that the sender of the funds is not necessarily seeking to disguise their origin, but rather to reimburse and deliver operational funding for criminal activities.

5.3.2. Assisted plus Enabled Crime

Despite the focus on money laundering, mobile finance products face a far more pervasive challenge from traditional criminal behavior that has either been enabled or accelerated by the adoption of MFSs. In 2011, the Kenyan National Police highlighted “the use of information and communication technology to perpetuate criminal activities” as amongst the factors contributing to criminality in the country. This challenge is only likely to grow with MFS adoption. Three primary types of criminality, as observed by (STATT, 2012), could increase through MFSs in Kenya and Tanzania: fraud, extortion and corruption.

In Bangladesh as well, the increasing rate of mobile phone based crime are creating havoc for the affected citizens. Criminals well-utilized the opportunity of new technology and the suffering increases mainly due to easy opportunity of false registration, limitation of LEA’s effort in using new technology, lack of instant access by police into transaction record. Introduction of Mobile Financial Services and its rapid uncontrolled growth also fuels into criminals’ ability to make best use of new technology in committing crime through various innovative forms.

5.3.2.1. MFS related Fraud cases:

5.3.2.3a Fraud through auto-theft, robbery and pick pocketing: Organized thieves stole CNG, motorcycle, auto-ricksha etc. and instead of/in addition to looking for customers for selling stolen property, they called owners and asked them to send money through mobile financial services like bkash, mcash etc. promising to return their goods. Sometimes, they return, mostly they don’t. Thus, they double their profit using new technology. They earn between Tk. 30,000 and Tk. 500,000 depending on the value of stolen property. [money flow chart]

5.3.2.3b ‘Hallo party’ fraud: Organized Criminals use SIM numbers look like mobile operators’ service number (e.g. 01919000000 or 01711123456) and pretend to be representatives of MNOs. Victims are informed about ‘winning’ a set of ornaments, a piece of land or flat in the capital or a dinner program with noble laureate. Sometimes, the criminals able to use special welcome tune or caller tune that represents a big company or a LEA. Victims were then asked to send a small amount of money - Tk 300 or Tk 3000 for ‘registration’. This is the start, once a victim becomes prey of the fraud group, they manage to exploit sometimes up to Tk 3000,000. Even people like retired senior civil servant or military officer, in-service Vice Chancellor of public university or member of civil society are found to be victim of this group; nevertheless, most of the criminals, who hardly passed high schools or colleges, managed to use greediness of victims, nevertheless, this should not be really an offence, if someone rely on technology or on the state-machineries that open-broad-day-light fraudulent activities can’t sustain or will not remain uncaught. Several villages of two districts in Dhaka division become infamous for the activities of a number of all-on-a-sudden-rich people amid most of the victims hardly ‘dare’ to put formal complaint to LEA to hide their very foolish greediness.

5.3.2.3c Fraud by ‘business company or firm’ or ‘family’ to job-seeker, bride-seeker or fortune-seeker: You want a job, follow ‘our’ job advertisement published in the newspaper or advertisement that are made public through pasting on the city-walls. You then apply – and done! You got the job!! Well, now, deposit security money through MFS and wait.

Case Study 5.3.2.1c: A wanted-to-be-groom responded to the advertisement published in a national daily with a view to marry an Australian based expatriate bride! He was quite soon ‘taken’ and .. ..‘Don’t have you passport (to fly to Australia with the bride)? Okay, send an amount of Tk. 5000 only’. CID later arrested the bride, her ‘father’ (actually husband), ‘uncle’ and ‘the match maker’ from Khulna Sonadanga. Look at the link chart of fraud group. CID after analyzing Call Detail Record, ‘discover’ number of victims and communicate with them to lodge regular FIR against the same group. [Link chart of

CDR]

5.3.2.2. MFS related Fraud plus

5.3.2.2a. Fraud & extortion by ‘Jenier badsha’ (Genie's king): Perhaps one out of 25 regular mobile users in Bangladesh has received phone call from ‘Genie as of the 4th sky’, who promise to give one big jar - full of ancient gold coins. What the call-recipient need to do, just to pay Tk. 25 for that very call through which the ‘Genie’ talked to the victim and caused loss of a human, whose mobile phone had been used for this super-natural communication. One out of 100 recipients of course, simply ignore the caller; but the very one, who is trapped will hardly recognize, how she or he is going to pay ‘Genie’ even by stealing or selling own properties. By and large, people from rural areas, mostly women become victims of such ‘Genie’. The crime start with fraudulency, but mostly continues with threat and extortion, where genie claims that victim herself or her son or husband or other important family member will instantly die, if she fail to comply genie’s order or if she communicate information of these activities to anybody else before ‘she was awarded with the jar full of gold coins. A northern district is infamous to run ‘Genie’ business, where from riksha-puler to upazila chairman, shopkeepers to MFS agents are involved in the crime (Police, 2014). There are numerous victims from all around the country who became their prey. But when a victim is to report to police, he or she has nothing but an unregistered or falsely registered SIM number and a tailored voice; nonetheless, the criminals change SIM and/or mobile sets after each successful operation.

5.3.2.2b. Master-of-all trades TV-saint: It’s a case of broad day light fraudulent activities using mobile, satellite TV and MFS technology. At deep night, a number of satellite TV channel (Masranga TV, Bijoy TV, Mohona TV, MyTV etc.) broadcast program on saints of various religions, who are simply any-problem-solver master-of-all-trades saint. The blessings of these saints or their ‘tabiz’ will certainly solve any kind of problem you are facing. You want to win a lottery or the heart of a your most desired girl or boy, or you want to defeat your enemy or control your husband or boss, or you want to get rid of sufferings from old diseases, what else, your TV saint is there; just call and get the problem solved. Mostly expatriates are target of such kind of TV propaganda, which are broadcasted between 0200 hrs to 0400 hrs of Bangladesh time. CID is investigating a case of one middle-east based expatriate, who lost Tk. 62 lakh (Tk. 6,200,000) through selling his all land and properties. Using high-tech and complex analysis process, a CID-team identified a number of Barishal based teams, who are obviously linked with some Dhaka based journalists of e-and print media personnel. CID awaits the amendment of law that now bar police to investigate any kind of fraud cases. Another Dhaka-based housewife had a severe brain stroke, after she understood that she had been cheated by the TV-saint amid by loosing Tk. 750,000 – which is of course, a lot of money for a middle-class house manager. [picture]

5.3.2.3. MFS related Extortion

5.3.2.3a Extortion by the name of Top terror: Businessmen, industrialists or service holders receive unknown call, where callers introduce themselves as top terror or their followers and demand toll from Tk 20,000 to Tk 200,000. Sometimes, the criminal is the neighbor’s iniquitous lad, sometimes it is a wanted criminal calling from the land-border with neighboring country. Criminals use the terrors’ names that receive more media coverage [‘Haven’t you see in the last week on TV; this is we - who have committed that murder, man’].

5.3.2.3b Abduction/kidnapping for ransom: Organized group abduct a man or kidnap a child; and ask for money. There is another shorter version, where criminals offer a short-lift to a home-goer employee or a city dweller (a distance of 10 km from Kawranbazar to Uttara for example), take him into their vehicle, using victim’s mobile phone and compel the victim to call spouse or other family member to pay a ‘tolerable’ amount of money (Tk 15,000 or 30,000). The criminals actually keep on roaming around the city or in the highway, release the victim along with his mobile phone just after ransom money is paid into criminal’s MFS account. No hideout, no watchman, no feeding arrangement for victim. This is crime with one vehicle and an MFS account number; and by and large the number is the one personal account of a nearby MFS agent!

5.3.2.3c Abducting/Kidnapping abroad and ransom money from expatriates’ relatives: A group of Iran based human trafficker trapped many Bangladeshi expatriates working in the middle-east to Iran and compelled the relatives of victims to pay ransom money to their Bangladeshi agent through MFS.

Case Study 5.3.2.3c. CID arrested a Bkash agent Farid with 87 SIMs - all with falsely registered Bkash personal account. Suspect Farid was account opener as agent and also user of all these 87 accounts. Farid didn’t maintain any register that he supposed to maintain according to direction of Bkash as well as to the mandatory regulations set by the central bank. Several crore Tk. was laundered through this Bkash agent from scores of victims’ relatives to trafficker’s family members – surprisingly one of whom is a college teacher, while Bkash agent Farid himself, is a school teacher. The same representatives (of trafficker) received money from another Halisohor-Chittagong based Bkash agent, who was also arrested by CID after conducting a number of operations.

5.4. For the purpose of articulating a comprehensive picture of MFS related crime, Appendix-1will give a concise idea on ‘Fraud in Mobile Financial Services’, which was prepared through an integrated study (Muridi, 2015).

6. Survey on Usage of MFS by Garments’ Workers

Bangladesh Bank, our central bank, has been exploring various methods to enhance access to formal financial services for workers. In September 2013, it directed commercial banks to open special accounts for garment workers through which they can receive their wages. We have 4 million factory workers in Bangladesh and they almost exclusively are paid in cash, where 86% percent of them do not have access to formal financial services.

Financial Inclusions Insights (FII) that covers eight countries in Africa and Asia at different stages of the development of digital financial services also has queer findings through a number of Focused Group Discussions:

a. Mobile phone and mobile money use

1. Most workers own a mobile phone and know how to use basic features, but many ask for help with reading text messages (SMS) or using apps, which are generally not in colloquial Bengali.

2. Workers are not allowed to use phones inside the factory.

3. About awareness of mobile money –particularly bKash –is high, but it is perceived only as a money transfer service. There is little awareness of the other services among both users and nonusers.

4. Most mobile money users in the study use over-the-counter money transfers and do not have registered accounts. [This is actually zero-length m-loop, you have already known]

b. Salary payment method

1. Garment workers are generally satisfied with the current payment method (cash).

2. It takes two to 10 minutes to disburse salaries to individual workers and is perceived as efficient.

3. Workers value getting paid in cash and having instant access to their money since most of their regular transactions, such as paying rent and buying groceries, are also conducted in cash.

c. Financial behaviors

1. Most regular transactions are centered around rent, food, savings deposits, paying back regular vendors who sell them goods on credit, and remittance transfers. [You have to create necessary environments for increasing the length of m-loops considering these sectors of expenditure. That is, if garments workers being paid through MFS can find their environment to pay rent, deposit savings, incur debt and transfer remittance through mobile financial service, hopefully, they will be more interested here. But before that, you have to effectively stop the anomalies like false registration, OTC dealing etc. Give a message to your clients through your well trained professional agents that they are being dealt with sincerity; hopefully it will keep your clients and save their money.]

2. Most routine transactions are conducted in cash within a radius of 2 km of home/work, and most are done with relative ease.

3. Many workers use a savings deposit plan with a bank or with the factory they work in. They must deposit the same amount of money on a monthly basis to reap the interest earnings, at the end of a specified number of years. Factories also offer loans to workers in the form of interest free advances on future earnings.

d. Potential for digitizing salary payments and extending mobile money use

1. Workers are reluctant to embrace digital salary payments mainly because it requires an additional step --going to an agent to access their cash. They are concerned about the possibility of waiting in long lines, lack of cash at agent locations and potential fraud issues.

2. Despite concerns about fraud and inconvenience, many workers are open to the potential use of mobile money if they can conduct all mobile money transactions without incurring additional transaction fees.

3. Some participants were able to identify transactions that might benefit from digitization. For instance, many place a high priority on going to the bank as soon as they get their salaries so they can meet their monthly deposit deadlines for their bank savings plans. Using mobile money to immediately transfer money from their salary directly to their savings plan could help make this transaction smoother.

A survey conducted by (Nupur, 2015) reveals that workers are not interested to be paid in mobile money in spite of the fact that most of them are using mobile financial system for sending remittance, for a number of reasons:

a. Drawing salary conventionally costs no money, where MFS based salary costs money for each cash-out; no one wants to lose money from one’s own income.

b. To them, loss of mobile phone will make it difficult to draw one’s own money;

c. ‘Robbing your mobile phone is not robbing your money’ doesn’t assure them. Massive usages of MFS may drive robbers to rob both mobile phone and mobile money by forcing them to get their PIN code followed by drawing/transferring their money. Moreover, losing both mobile phone and money is a huge loss for a worker, even if a cell phone costs less than Taka 1000 (US$ 12).

d. Densely inhabited workers in a small area will cause a long queue in agents’ premises, which may turn into major discomfort to the workers. Also, a group of persons living in a low profile may find their new defacto-salary boss into agents, which is of course another issue of discomforts.

e. Very limited opportunity for usage of MFS in mobile payment and mobile banking, where market is not developed enough for mobile payment in their field of expenditure and the rate of interest for mobile banking is 1% to maximum 4% hardly attracts consumers.

f. Being paid through mobile means a long queue in local MFS agents’ compound with uncertainty for getting cash in-time;

g. Mobile money are not really usable directly in the local market, e.g. groceries, public transport, etc. where they use to spend their money;

h. Each time they cash-out they are definitely lose their money as service charge. They don’t really want to lose their money from salary.

i. Temporary kidnapping along with mobile phone compel a possible victim to transfer easily their money along with mobile phone to be robbed, as it is not very difficult for robbers to get their PIN/security code from an abducted victim.

Both the studies show that Mobile Service Providers as well as the respective controlling authority are yet to get the confidence of the customers by ensuring the safety and security of their e-money.

Consumers’ International (Consumers International, 2014), a registered UK charity and the world federation of consumer rights groups observes a number of consumer protection MFS-related issues which have been brought by members and by industry colleagues. Consumers’ International works to ensure that consumer rights, with over 240 member organizations spanning 120 countries,

1. Lack of tangible proof of payments (e.g. receipts), with the consequence that in the case of a dispute the consumer will have no evidence to support a claim that a specific payment has been made.

2. Unreliable mobile account crediting systems.

3. Lack of technology standard.

4. No specific regulatory framework

5. No independent ombudsman

6. Lack of currency

7. Dormant assets.

8. Digital certificates.

9. Excessive prices of transfers (remittances)

10. Accessibility.

In Bangladesh, some of them may be turned into less-focused issues; however, there are other issues that need to be addressed without delay.

Considering more than 4 million factory workers, who currently are paid almost exclusively in cash and out of 86% of which have no access to formal financial services, Financial Inclusions Insights (FII) conducted a research on the use of mobile money and other digital financial services (DFS), and the potential for their expanded use among the poor. Bangladesh Bank also directed commercial banks to open special accounts for garment workers through which they can receive their wages.

But FII findings on mobile phone and usage of mobile money are really interesting. It observes that: Most workers own a mobile phone and know how to use basic features, are generally satisfied with the current payment method (cash) and are reluctant to embrace digital salary payments.

Recommended measures are:

a. Garments workers should not be charged for cashing (out) their salary. Agents may be paid by the banks for such service at least for the salary part that they receive from the employer; and bank may charge the employer through a mutual understanding through MOU.

b. Law enforcer should be trained and equipped properly so that any kind of crime either digital or physical can be quickly addressed by Police with the systematic, professional and immediate support from respective bank authority. Please don’t forget, when one of your victim (either client or agent) lose money through kidnapping, theft or cheating – in whatever form it is , the fact is that the robber, the cheat or thief is officially your another client. So, from client side, clients want safety and security of their own money.

c. Mid managers could be made first target for introducing MFS based salary fully or partly on pilot basis. This may in turn give a sense of aristocracy to the garments workers when they will be brought under MFS based payment.

d. Banks or MFS institutions must develop MFS markets for transactions of m-loops of length more than two. The existing market with m-loop length 1 seriously hampers its further development and keeps MFS as nothing but courier service rather than banking service; and market with zero loop is nothing but haven for money laundering causing serious threat for mobile money users.

7. Legal provisions along with above-board barriers in investigating Money laundering cases:

7.1. There are number of laws which are directly or indirectly can be applied against the offences mentioned in this paper. But the major laws that deal with money laundering issues is Anti Money Laundering Act 2012, nonetheless, which is yet to empower police but ACC to investigate money laundering cases. Anti Money Laundering Act 2012 empowers mostly Anti-Corruption Commission to investigate all kind of money laundering cases, in addition to deal in its own mandated crimes corruptions and briberies, not to tell that corruption and bribery issues are exclusively given to ACC and only ACC, which is not the standard practice in most part of the world. You can remember an allegation against an ex-minister of Bangladesh was investigated by Canadian Police, even though Canada do have their own Anti Corruption Agency.

7.2. A CID official expressed: